In this article, I explore the leading paradigms of atonement and salvation in Christianity, both mainstream and alternative. I also make the case for my conviction that conventional Christianity, especially in its more conservative forms, has been too harsh and unforgiving in its understanding of sin, atonement, and salvation

Introduction: The Law of Sacrifice

The rock opera “Jesus Christ, Superstar” opens with the line, “Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ, who are you, what have you sacrificed?” In her excellent book, Esoteric Christianity, Annie Besant talks about the Law of Sacrifice – not just from the narrow perspective of Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross at Calvary, but also in a broader metaphysical sense. Sacrifice is a basic principle or process that is necessary to attain anything of true or lasting value and worth in life, and Jesus’ sacrifice is symbolic of that core spiritual truth. If you want to achieve anything significant in your life, you must sacrifice the time and effort to do so. A pregnant woman sacrifices nutrient substance from her own body to grow a fetus in her womb, and even after birth, the parents of the child sacrifice a lot of time, effort and expense in raising the child. Sacrifice is even necessary for the physical health of our bodies, in that all metabolic processes in the body are either catabolic, in which structure and nutrient substance is sacrificed to produce energy, or anabolic, in which energy is used or sacrificed to build physical tissue and structure. And at the end of one’s life, one makes the most radical sacrifice of all, and gives back one’s whole body to Mother Earth and the recycling processes of Nature.

When you think of it, the Law of Sacrifice pertains to so many core spiritual truths of Life. For example, it is more blessed to give than to receive, and what is giving but voluntary sacrifice for the greater good? Jesus Christ said those who try to keep their life would lose it, but those who seek to lose their life for his sake would find it (Matthew 16: 25, Luke 17: 33). This is probably the closest thing that we have to a Zen Koan in the Christian scriptures, but it is a spiritual truth; try to hold onto anything too tightly and you will lose it, but seek to give it to a worthy cause and you will find the way, and grow spiritually. This also relates to the spiritual principle of selflessness or non-attachment. Everything that we have is actually on loan to us from God, so use it wisely – even your life. Jesus Christ made the ultimate sacrifice on the cross at Calvary, but so did heroic soldiers dying on the battlefield for love of country, and so did martyrs like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King – without all the theological underpinnings that go along with Jesus’ sacrifice in Christianity. In all probability, the Jerusalem Church of Jesus’ earliest Jewish followers merely considered their rabbi and spiritual teacher to be a martyr.

Before Jesus could go to his Father and attain the greater Life that awaited him in His heavenly Kingdom, he had to give up the ghost of his earthly life. And so, it is quite instructive to compare the different canonical gospels to see what Jesus’ final words were on the cross before he died. In Mark, the earliest gospel to be written, Jesus says, “My God, My God, why hast thou forsaken me?” Jesus says the exact same thing in Matthew, the second gospel to be written, as well. In Luke, the third gospel to be written, Jesus is much less anguished, and much more confident and self assured; he magnanimously forgives those who are crucifying him, tells one of the thieves that is being crucified with him that they will soon be together in paradise, and finally commends his spirit into the hands of his heavenly Father. In John, the last gospel to be written, Jesus simply says, “It is finished” when he gives up the ghost, but first, he unites his earthly mother with her adopted son while on the cross. As Jesus grows calmer and more self assured in his final trial upon the cross, we can see Christian theology about Jesus’ divinity and the necessity of his sacrificial atonement quietly developing in the background.

A Dual Legacy of Sacrifice in Christianity

By now, it should be clear that Christianity is a religion that places a lot of emphasis on sacrifice. Many Christians take the position that blood sacrifice was absolutely necessary for the remission of sins in Old Testament Judaism, even to the point of taking the verse of Leviticus 17: 11 – For the life of the flesh is in the blood… as a biblical verse declaring the absolute necessity of blood sacrifice for the remission of sins, but Jewish rabbis counter that that verse, and indeed the whole seventeenth chapter of Leviticus, is about the kosher dietary laws, and the necessity of draining all the blood out of meat before eating it – it has nothing to do with blood sacrifice. The fact is that Old Testament Judaism allows for other methods of atonement besides blood sacrifice. Consider the following verses:

For thou desirest not sacrifice; else I would give it: thou delightest not in burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and contrite heart, O god, thou wilt not despise.

– Psalms 51: 16 – 17

All this Christian insistence on the absolute necessity for blood sacrifice in Old Testament Judaism has one aim or purpose; it is to provide the doctrinal background or justification for Jesus Christ’s atonement on the cross at Calvary, which many, if not most, Christian believers consider to be the ultimate blood sacrifice, which rendered all further blood sacrifice to be unnecessary and obsolete. Nevertheless, Jewish rabbis continue to insist that Christians are making way too much of blood sacrifice, and assigning to it a place and stature that it never had in Judaism. All this talk about blood sacrifice, and bathing in the blood of Jesus, is frankly quite abhorrent to most Jews, who consider such a preoccupation to be quite primitive and barbaric.

What most Christians are totally unaware of is that their religion has inherited a dual legacy of sacrifice. Ritual sacrifice of animals was a common practice in Judaism, but Jews didn’t consider it to be the only way of approaching God for forgiveness. Sacrificial rituals were also an important part of many of the old Greco-Roman mystery religions that preceded Christianity. Although the particulars of sacrificial ritual and its symbolic significance and mythology varied from one mystery religion to the next, a common underlying theme in many of them was that of the solar vegetation god, who selflessly sacrificed and gave of himself in the harvest so that the people could live. His gifts were often symbolized in a loaf of bread and the grain from which it came, as well as wine, which is made from the fruit of the vine; both of these were ripened and brought to full fruition by the sun’s generous bestowal of light and heat. The sun would ripen the grain and the grape, which would then be harvested and sacrificed for nourishment; with the following year’s planting season, the agrarian cycle would begin anew.

Consider the Christian Eucharist. We are told that the bread is Jesus’ body, which has been broken for all, and that the wine is Jesus’ blood, which has been shed in the new covenant. What is this but the solar vegetation deity selflessly giving himself to us? This might deeply offend the religious sensibilities of many conservative Christians, but when we get beyond the particulars of theology and doctrine, this is essentially what it is: the pouring of old wine into new wineskins, so to speak. Paul is our oldest New Testament writer, and his account of the Eucharist (1 Corinthians 11: 23 – 27) even precedes the accounts given in the gospels. Paul came from the city of Tarsus in the Roman province of Cilicia, which was a big center for the cult of Mithraism in Paul’s day. One of the core rituals of this old mystery religion, which was an early rival to Christianity, was a Eucharistic meal of bread and wine that closely resembled the Christian rite – 1. Although the mere notion of cannibalism, even in symbolic form in the Christian Eucharist, was strongly abhorrent to most Jews, Mithraism got even gorier and more graphic than Christianity; besides drinking blood in symbolic form as wine, there was another Mithraic ritual, called the Taurobolium, in which the devotee would actually bathe in the flowing blood of a sacrificed bull. – 1.

Paradigms of Atonement and Salvation in Christianity

“Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ, who are you, what have you sacrificed?” That is the basic question that the various sects and denominations of Christianity attempt to answer in their various doctrines and theories about atonement and salvation. The prevailing general model is that Jesus’ atonement on the cross at Calvary was some kind of sacrifice, and that what Christ sacrificed himself for involved Original Sin and the redemption of mankind back into God’s Kingdom. But exactly how that worked, and exactly what was offered for what, varies from one Christian sect or denomination to the next. Let’s examine what the most common paradigms of atonement and salvation are in more detail:

Penal Substitution: The Prevailing Paradigm in Western Christianity

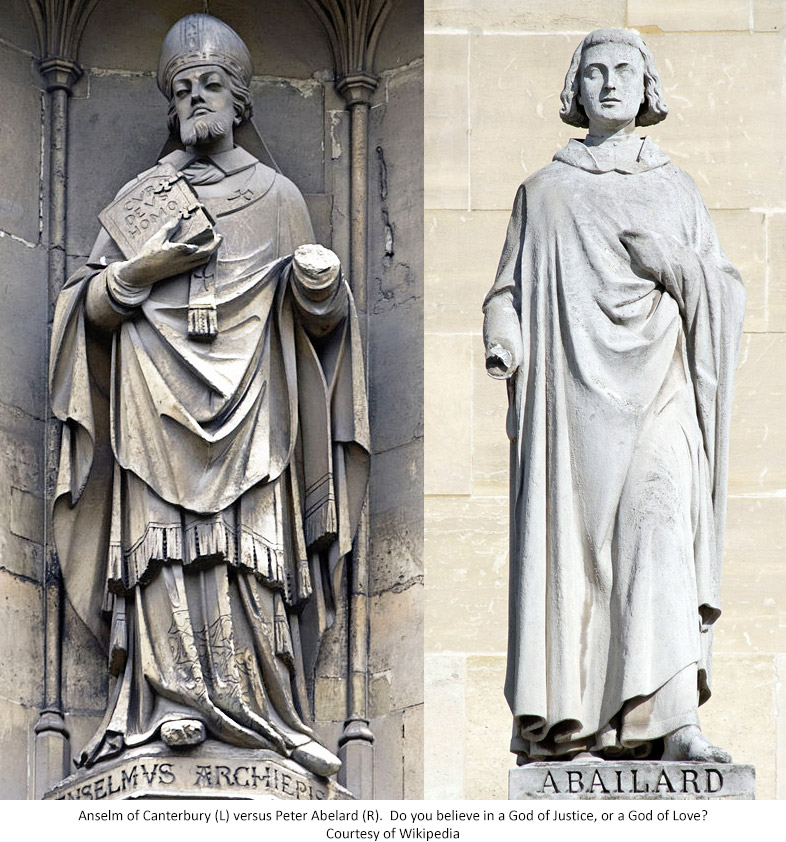

The most common way of seeing man’s fallen state in Western Christianity, in both its Catholic and Protestant forms, is in legal or transactional terms, as a debt or penalty that must be paid to God if one is to be saved. And Jesus Christ, in offering himself up as God become Man to God the Father, paid the ultimate and perfect price to redeem the sins of all mankind, both original and otherwise, in his crucifixion and resurrection. The theory of Penal Substitution, which could also be called Substitutionary Atonement, since Jesus died and paid the penalty in our place, had its origins with Anselm of Canterbury, an eleventh century English cleric who first put forth the doctrine in his theological treatise Cur Deus Homo, or Why God Became Man. – 2. Besides being called Penal Substitution or Substitutionary Atonement, Anselm’s theory of atonement and salvation is also called Satisfactionism or the Satisfaction theory of Atonement; sounds like an old Rolling Stones song, doesn’t it? The basic idea was that the Original Sin and the fall of Adam and Eve deeply offended God’s perfect sense of righteousness and justice, and only the death or sacrifice of someone who was fully God as well as being fully man – in other words, Jesus Christ – could atone for human sin and satisfy God’s perfect and unyielding sense of justice.

Despite its widespread popularity and acceptance within Christianity as the dominant paradigm of atonement and salvation, there are several problems inherent in this paradigm. In insisting that only another – Jesus Christ – can atone for our sins, and not ourselves, Penal Substitution goes against what is usually a foundational principle of human ethics, which is personal responsibility and accountability for our own actions and choices in life. This principle of personal responsibility and accountability is also upheld in multiple verses from the Jewish Scriptures, or Old Testament (Deuteronomy 24: 16; Ezekiel, chapter 18). Also, with its central emphasis on satisfying the perfect sense of justice of an offended God, Penal Substitution makes God out to be very petty, tyrannical and thin-skinned; it also makes God out to have a passive – aggressive complex: Being omniscient, God would have known that His creation, man, was imperfect and prone to sin and error when He created him – then why all the divine outrage when man winds up sinning? Penal Substitution also puts two persons of the Holy Trinity, God the Father and God the Son, who are supposed to work harmoniously together, into direct conflict with each other: God wanted to shoot me straight to hell for all eternity, but Jesus took the bullet for me.

The First Epistle of John famously says that God is Love, but God as envisioned in the Penal Substitution theory of atonement and salvation is like an abusive father giving out mixed messages: If you don’t accept my Son, you will fry in hell for all eternity, but don’t worry – God loves you! Do you really believe in a God who acts more like a gangster or a kidnapper, with his Son having to offer himself up as a ransom for our sins, or a God that behaves like a cosmic dictator? God, like Al Capone, is making you an offer you can’t refuse – accept my Son, or fry in hell for all eternity; this puts God on a very low moral or ethical level. This, I feel, is crossing over a critical moral line in trying to put the hard sell on Christianity. A friend of mine, who is a liberal and metaphysically inclined Christian minister, once joked to me that, if Jesus had taught the doctrine of Penal Substitution, the final scene of the parable of the Prodigal Son would have ended with the father saying to his son: Hold on – I gotta go out and kill your brother before I can welcome you back into the Kingdom!

Peter Abelard and the Moral Influence Theory of Atonement

After we took a look at Satisfactionism, we now move on from that Rolling Stones song and go to “The Power of Love”, which was the theme song from the 1980s hit movie “Back to the Future”. The key difference between liberal Christians and conservative ones is that liberal Christians believe more in a God of Love, whereas conservative Christians believe more in a God of Justice, as portrayed in the Penal Substitution / Satisfactionism theory of atonement. I personally believe more in a God of Love than in a God of Justice; that’s not just because I am more liberal in my views, but also because of what I see as a fundamental truth: Everyone easily understands what love is, and all human beings respond to it instinctually, but when it comes to justice, the question arises: Exactly whose idea of justice are we talking about? Of course, when conservative Christians talk about a God of Justice, they are talking about the petty and wrathful God of the Satisfaction theory of atonement, who is all too eager to send us straight to hell at the slightest offense to His perfect and infinite sense of divine justice. But maybe this is not really the way God is, but just a projection of these conservative Christians out onto God. God says in the Book of Isaiah:

For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts.

– Isaiah 55: 8 – 9

This brings us to the God of Love, the power of love, and to the Moral Influence theory of atonement, which was put forth principally by Peter Abelard, an illustrious Christian philosopher and theologian of the twelfth century. Coming as he did about a hundred years after Anselm of Canterbury, Peter Abelard’s Moral Influence theory of atonement can be seen as a reaction to, or backlash against, the Satisfaction theory of atonement put forth by Anselm. Peter Abelard stressed the moral influence of Christ’s boundless love and compassion for mankind in offering himself up on the cross, and saw it as having a transformative moral influence that attracted spiritually hungry souls who, inspired by the sheer power of Christ’s transcendent love, had their essential moral natures fundamentally changed to endure and transcend all obstacles in a spirit of infinite love and patience. Christ’s infinite love and compassion can also inspire the transcendence of fear, even the fear of death. Paul’s beautiful sermon on Love from his Epistle to the Corinthians seems especially relevant here.

Peter Abelard stressed the moral example that Christ was offering to all mankind as he selflessly gave everything he had on the cross. Like Jesus, every one of us will eventually come to that point at which we must relinquish everything we have in life and make that transcendent leap of faith into God’s heavenly kingdom, where Jesus has told us that he has prepared a place for us (John 14: 2). In the idea that Christ set a shining moral example for the rest of humanity to follow, Peter Abelard was, in effect, echoing the sentiments of Bishop Arius that the great virtue of his conception of Christ was the great moral example it offered to struggling humanity. Arius was declared a heretic at the Council of Nicea, but his ideas would persist in Christendom for at least a hundred years after his condemnation. The Jesus hymn in the second chapter of Paul’s Epistle to the Philippians portrays a humble and self-emptying Christ who gave his all, and was subsequently exalted because of the moral virtue of his sacrifice. Fast forwarding to the current New Age, the Jesus of A Course in Miracles puts forth the idea of Love as being diametrically opposed to fear, and therefore being fear’s sovereign remedy and antidote.

The Gnostic Perspective: Are You Worshiping a Dead Man?

One of the key points on which the early Gnostic Christians took issue with those who were in the proto-orthodox school of Christianity was their excessive preoccupation with Jesus’ crucifixion, and its redemptive power for all who believed in it. For them, this was like worshiping a dead man; for the Gnostics, it was Jesus’ secret teachings, and the illuminating wisdom that he imparted through them, that had real saving power. The canonical gospels of the proto-orthodox school all have their climax with Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, even to the point at which what goes before can be seen as only a prelude or lead-up to the main event. The Gnostic Gospel of Thomas, on the other hand, says nothing about Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection; it consists only of 114 wisdom sayings of Jesus. The author of the Gospel of Thomas says that he who truly understands these wisdom sayings shall never taste death. Contrast this with the teachings of Paul; for Paul, it was all about Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection. Paul spends hardly any time discussing Jesus’ actual teachings; maybe an important reason for this is that he was never a personal disciple of Jesus.

Another cynical perspective that religious skeptics can take regarding the Christian religion is that it is primarily a death cult. If you don’t believe me, it could be argued that lesson one in the catechism of conventional Christianity starts out with: Why did Jesus die? The answer, of course, is that Jesus died for our sins; that’s simple enough for all to understand. If you’re really dogmatic and heavy handed in your Christianity, the initial question becomes: Why did Jesus have to die? Then, if you’re a real religious cynic regarding Christianity, you could say that God sent His Son on a suicide mission – which is an interesting way of looking at things indeed. If I were to say one way or another, I would say that most mainstream Christians may have a better understanding of Jesus’ sacrifice or atonement on the cross than they do of his actual teachings; chalk that up to the all-pervasive influence of Paul.

Do you focus more on Christ crucified, or on the risen Christ? I would say that, for most Christians, the central focus is on the crucified Christ, suffering for our sins. How else would you explain the phenomenal success of a gory, blood-and-guts crucifixion movie like Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ”? For Christians with a more esoteric or spiritual orientation, the focus is primarily on the risen Christ. “Why do you seek the living among the dead?” The Eastern Orthodox Church has an interesting perspective on Christ’s resurrection: Death could not contain him. I like that. Christ’s selfless Love, the awesome spiritual power that dwelled in him, was way stronger than death. The Christian passion narrative can also be seen as providing a set of esoteric instructions for Christians facing their own death and mortality, and seeking to understand how to transcend and overcome it.

There’s yet another curious aspect to this Christian preoccupation with death, and that is the Christian belief that death came into the world with the Original Sin of Adam and Eve. Paul famously wrote that “The wages of sin is death.” (Romans 6: 23). Did Adam and Eve really become mortal because they sinned? Just to offer up a conflicting bit of evidence here, God, when He creates man and woman for the first time, tells them to be fruitful and multiply. Now, strictly speaking, procreation and the begetting of offspring are only really necessary if one is mortal, with offspring needed as one’s replacement or progeny. In support of the conventional Christian position, God did indeed tell Adam and Eve that on the day that they ate of the forbidden fruit, they would surely die. And then, God expels Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden to keep them from eating from the Tree of Life, which would make them immortal. So, the Book of Genesis is not unequivocal when it comes to sin leading to death. I personally believe that death is, above all, a natural process, which is the end result of aging and the human life cycle. And what’s so bad about that?

When I was younger, I had a spiritual teacher, namely Paul Twitchell, the founder of Eckankar, who also called Christianity, at least in its conventional form, a death cult. Paul Twitchell called Eckankar the Ancient Science of Soul Travel, and what that entailed was traveling or journeying out of the body as Soul or Spirit, to explore the heavenly worlds while we were still living. If you do not gain spiritual knowledge or experience of the heavenly worlds while you are living, said Paul Twitchell, where is the guarantee that you will achieve it after death? Jesus tells Nicodemus that what is born of the Spirit is Spirit, and what is born of the flesh is flesh – definitely, most of us identify too much with our physical bodies, and not enough with Soul, or Spirit. Maybe that’s really what the Christian Gnostics were seeking – actual experiential knowledge, or gnosis, of themselves as Soul or Spirit during this lifetime. Why worship a dead man, and not the living Christ within you?

Faith versus Works in the Quest for Salvation

As a whole, the Christian spiritual tradition comes down heavily on the side of faith in the quest for salvation, largely due to the formative influence of Paul. Regarding this, there is a key passage from Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians:

For by grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves; it is the gift of God: Not of works, lest any man should boast.

– Ephesians 2: 8 – 9

Yet James the Just, who both Luke, in the Book of Acts, and Paul, in his Epistle to the Galatians, call the brother of the Lord (Jesus Christ) weighs in with a dissenting opinion in his epistle:

But wilt thou know, O vain man, that faith without works is dead?

– James 2: 20

Faith is made perfect through works, counters James, so that we may be doers of the Law, and not just hearers of it. Faith is brought to completion and perfection through works, according to James. When we back up our faith with works, he says, even the devil takes notice. The whole second chapter of James’ epistle is devoted to explaining why faith without works is dead, and how faith is completed and perfected through works. Since James was Paul’s predecessor, and was the patriarch of the Jerusalem Church of Jewish Christianity, which was the spiritual home of Jesus’ original followers, we can presume that the original Jesus movement, with its Jewish spiritual orientation and outlook, was Torah observant, and focused not just on faith, but also on works done in accordance with the Law. Paul, of course, despaired of even being able to fulfill the works of the Law with anything approaching the degree of perfection that it demanded; for him, faith, and faith alone, was the way to go. Different Christian sects and denominations place a differing degree of emphasis on works in relation to faith, but the Christian tradition as a whole comes down heavily on the side of faith.

So – how do we reconcile faith and works in the quest for salvation? What is the best way to understand the two, and their relationship to each other? I believe that faith and works are the two sides of the same coin, with both together pertaining to the quest for salvation; faith is the receptive, Yin side of the coin, since it is a gift from God, as Paul states, whereas works is the active, Yang side of the coin. The prevailing Christian perspective is that faith must come first, and open us up to God’s grace, through which we are empowered to take the next step in works. Ideally, it should be like a walk towards god with both feet, with faith begetting works, and works in turn begetting more faith. Faith strengthens one’s humility and receptivity to God’s grace, whereas works strengthens one’s spiritual will and resolve to do the right thing. We can tell that the Jewish spiritual tradition takes an active, Yang approach to salvation by God’s counsel to Cain in the fourth chapter of the Book of Genesis:

And the Lord said unto Cain, Why art thou wroth? and why is thy countenance fallen? If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? and if thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him.

– Genesis 4: 6 – 7

The final words of this passage regarding sin, “and thou shalt rule over him” provide the key to the Jewish spiritual tradition’s understanding of how to conquer sin – through an active exercise of one’s spiritual will. Show sin who’s boss! Through a cultivation of the will, one develops one’s spiritual muscles, so to speak. Contrast this with Paul’s attitude of spiritual despair at being a slave to sin, as expressed in chapters eight and nine of his Epistle to the Romans, and it is clear that the Jewish and Christian spiritual traditions are as different as night and day in this respect. So, with the Jewish spiritual tradition emphasizing works and will, and the Christian tradition emphasizing faith and grace, how shall we proceed? I believe that there are no hard and fast answers that are applicable to everyone regarding the faith versus works question; it is up to each individual to figure out how he or she should approach the use of faith versus works in his or her own spiritual development and quest for salvation, in accordance with their own inner spiritual nature and temperament. Listen to yourself, and to your own inner spiritual conscience and intuition on these matters.

Sin and Salvation in Eastern Orthodox Christianity: Spiritual Healing and Integration

Now, we come to the Eastern Orthodox understanding of atonement and salvation, which I consider to be the gold standard among all the various paradigms of atonement and salvation that I have seen. Whereas, in Anselm’s paradigm, the emphasis is on God, and not offending God’s perfect and eternal sense of justice, in the Eastern Orthodox understanding, salvation does not center on God and satisfying His sense of divine justice, but rather, the central focus is on the spiritual healing of the wayward and fallen soul, and its reintegration back into the Kingdom of Heaven, which is where it actually belongs. When you come to think of it, God, as the Lord and Creator of the universe, is perfect, whole and complete within Himself, and lacks nothing. The Eastern Orthodox Church does not see man’s fallen state in legalistic or transactional terms, as a debt or penalty that must be paid, but rather as a condition of estrangement from God. The church is seen as a spiritual hospital for ailing souls.

Sin, in the Eastern Orthodox understanding, is not primarily an offense against God; it is primarily that which hurts the sinner, cuts him off from the healing Light of God, and estranges him from God’s Kingdom. If God had primarily wanted Jesus to pay the price for our sins, and for full restitution to be made in a legalistic sense, Jesus would have stayed dead as the penalty for our sins. But Jesus rose from the dead in the resurrection as his gift to us, by showing us the way to eternal life; that is God’s gift to us. In the Eastern Orthodox view, there is punishment and consequences for sinning, but the divine nature of God is not wrathful but passionless, applying the divine remedy with righteousness and justice, all the while seeking our spiritual growth and development like a loving father. It was in God’s infinite love and mercy that He sent His Son, Jesus Christ, to take on human flesh, for what is not assumed cannot be redeemed.

Whereas Western Christians, especially evangelical Protestants, see being saved as a single unique event or milestone in their lives, Orthodox Christians tend to view salvation more as a process of ongoing spiritual healing and reintegration back into God’s kingdom, and learning to take an ever closer walk with God. Theosis, or union with God via a full partaking of the divine nature, is the ultimate goal in Eastern Orthodoxy. The spiritual emphasis in Eastern Orthodoxy, I feel, is more on Jesus’ triumphant resurrection and victory over death, and not so much on the crucified Jesus, suffering for our sins. Many Western Christians tend to view the Eastern Orthodox Church as being somehow spiritually backward in relation to the West, because they did not go through a Reformation. But it must be remembered that the buying and selling of indulgences was one of the principal abuses that led to the Protestant Reformation, and these abuses grew out of the legal / transactional understanding of atonement and salvation that was fostered by the Satisfaction Theory of Atonement put forth by Anselm of Canterbury. Since the Eastern Orthodox Church never bought into the Satisfaction theory of atonement and salvation, it escaped these abuses, and therefore never had any need to reform them either.

I would like to leave you with an excellent video from an Eastern Orthodox channel on YouTube, which is about the Eastern Orthodox understanding of atonement and salvation:

Conclusion: Live and Let Live!

In my early twenties, I went through a difficult spiritual crisis; it was, spiritually speaking, a very dark time in my life, where I felt that I had deeply offended God, and didn’t even deserve to live. I became very depressed, and didn’t even want to live any more. But one night, in the middle of the dream state, I was led to a place where I was blitzed – or blessed – with the healing Light of God. From that moment on, I intuitively knew that there were divine powers that be in the universe, but rather than having any spiteful or vindictive intention, they were only loving and benevolent, desiring only my highest good. After that deep spiritual vision of mine, my mental and emotional state started improving, until finally, I was able to pull myself out of that dark hole and begin my spiritual healing.

And so, my heart goes out to all conservative Christians who are struggling under the burden of an image of God that is unduly wrathful and vindictive, whom they envision as being ever ready to punish them on the slightest pretext. Chill out for a minute! Have you ever considered that God’s true attitude towards your human condition, and all its tribulations and predicaments, might be more one of live and let live? Why wouldn’t God be more interested in helping you than in condemning you? Wouldn’t God’s attitude be more one of wanting to see you do well, as it was back when he counseled Cain, shortly after the fall? If God was truly so eager to punish and condemn, then why did God the Son pardon the woman who was accused of adultery?

***

Sources: