Think you know the Christian doctrine of Original Sin? Take a deeper look. What you discover may surprise you as I explore the history of this doctrine as well as its many ramifications, both positive and negative.

Introduction: What Is Original Sin?

Most people would agree that nobody’s perfect; there’s an old proverb that says, “To err is human, to forgive, divine.” All human beings make mistakes from time to time, and nobody is perfect. To many, especially those of the conventional Christian persuasion, to say that nobody is perfect may be a huge understatement. All major world religions have some theory or doctrine to explain a human being’s considerable capacity for error and wrongdoing; in Christianity, that doctrine is Original Sin. Although all religions have some concept of sin, Christianity is the only major religion, to my knowledge, that goes so far as to deem the original, basic nature of man to be sinful, through the doctrine of Original Sin. In his epistles, Paul put forth the doctrine of Original Sin in its rudimentary form, as Christ being the second Adam, who redeemed us all from the taint of the Original Sin committed by the first Adam when he and Eve ate from the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden. In the fifth century AD, Augustine of Hippo put the finishing touches on this doctrine and brought it into its present form.

“As a man thinketh, so is he” (Proverbs 23: 7). That’s one verse from the Bible that it is pretty near impossible to dispute – and it is quite relevant to ponder when considering the doctrine of Original Sin. If you think, in your deepest heart of hearts, that your basic nature is sinful or evil, that belief will negatively color or affect everything you say and do, and everything you perceive as well. In other words, you will see the world through sin colored glasses. Furthermore, if you believe that your own nature is basically sinful, then you will tend to project your own feelings of sinfulness about yourself out onto others, and assume the same wicked, sinful nature for them as you do for yourself. With such a negative perception of others, you run the risk of perverting the Golden Rule into something like, “Do unto others before they do unto you.” All told, it seems to me that the doctrine of Original Sin has destroyed more human potential than just about any other Christian doctrine that I can think of. Why has Western Christian civilization been so prone to committing campaigns of genocide on the various indigenous peoples it encountered around the world? Maybe the projection of wickedness out onto others via a belief in one’s own Original Sin may play a larger role than most people think.

Was it really Adam and Eve’s Original Sin in the Garden of Eden that is responsible for our evil, sinful nature – or is it merely the belief that this is so that is really doing all the damage? Sorting this out with any degree of precision and objectivity may be next to impossible to figure out; like a troublesome weed, the whole Original Sin thing may be extremely difficult to pull out by its roots, and many people who believe they have done so may just have reasoned it out on an intellectual level – emotionally and behaviorally, they may still be held relentlessly in its grasp. I vividly remember the evening when Mrs. Nagata, my homestay mother when I taught English in Japan, peered up at me from behind her reading glasses and asked me, point blank, whether I believed that the original nature of man was basically good or evil. It seems like she had sensed that I really wasn’t free of the whole Original Sin thing on an emotional or subliminal level. Mrs. Nagata was a keen student of world philosophy and comparative religion, and we had many profound discussions on things like sin and virtue, even into the late night hours; she also taught me a lot about the approach to sin and error in her native Buddhism, which, even though it does not have the doctrine of Original Sin, is still no lightweight in tackling the problem of human sin and error. God – and Buddha – bless Mrs. Nagata!

The Origins of Original Sin – Mythical and Historical

To most believing mainstream Christians, the story of Original Sin goes all the way back to Adam and Eve, the first man and the first woman, back in the Garden of Eden. It all started, the story goes, when Eve got Adam to eat of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, which God had forbidden them to eat. And to most conservative Christians, who tend to have an authoritarian mindset, the mere fact that Adam and Eve disobeyed God and ate the forbidden fruit was a grievous enough sin to curse all of mankind for generations and generations to come. In fact, most conservative Christians never ponder the deeper meaning of the Adam and Eve story and its outcome beyond the simple fact that Adam and Eve disobeyed God. To them, it’s all black and white, and not open to interpretation or debate. Get on God’s bad side, and you suffer. But the fact is that the Adam and Eve story is open to alternative or allegorical interpretations. The most basic proof of this reality is that, although the same Adam and Eve story is also in the Jewish Bible, or Tanakh, Jews don’t derive the same lesson of Original Sin from it that Christians do.

Simply put, the Adam and Eve story can be interpreted on an allegorical level as a kind of myth, or sacred allegory, if you prefer, that explains how the whole karmic drama of human earthly life started, with man and woman reaping the fruits or consequences of their own good and evil actions – the knowledge spoken of when it comes to the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil is experiential knowledge, not intellectual knowledge or didactic learning. It must also be remembered that Adam and Eve, at that point, were totally innocent of any mundane life experience, and innocence is a state that, by its very nature, longs to be filled with experience. Along with this hunger for experience came an insatiable curiosity, and so, Adam and Eve were very vulnerable to reverse psychology: If God said, “thou shall not eat…” the curiosity of Eve, and then Adam, drove them to eat the forbidden fruit. Because after the fall, Adam and Eve started to beget or procreate, the Adam and Eve story serves as the point of departure that leads eventually to the stories of the various biblical patriarchs later on in Genesis.

Perhaps the most direct evidence that the Adam and Eve story is not about Original Sin, or at the very least, that that was a later Christian interpretation of the story, is that the word “sin” is not even mentioned once in the whole Adam and Eve story. In fact, the first mention of the word “sin” doesn’t come until the fourth chapter of Genesis, in which God is counseling Cain to cheer him up before he commits the grave sin of murdering his brother:

And the Lord said unto Cain, Why art thou wroth? And why is thy countenance fallen? If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? And if thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door. And unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him.

– Genesis 4: 6 – 7

The fact that God counsels Cain on sin right before his grievous sin of murdering his brother Abel is indeed eerily prescient; definitely, God knows what is in the heart of man. God characterizes sin as a wolf waiting at the door, ready to ensnare him, but affirms Cain’s ability to rule over sin and conquer it. If Adam and Eve’s Original Sin in the Garden of Eden had rendered them and all their progeny to be hopeless slaves to sin, then God wouldn’t have given these words of counsel and encouragement to Cain in the first place.

The final sermon of Moses to his children, the Israelites shortly before his death, at the end of the Book of Deuteronomy, echoes this positive, upbeat spirit:

If thou shalt hearken unto the voice of the Lord thy God, to keep his commandments and his statutes which are written in this book of the law, and if thou turn unto the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul. For this commandment which I command thee this day, it is not hidden from thee, neither is it far off. It is not in heaven, that thou shouldest say, Who shall go up for us to heaven, and bring it unto us, that we may hear it, and do it? Neither is it beyond the sea, that thou shouldest say, Who shall go over the sea for us, and bring it to us, that we may hear it, and do it? But the word is very nigh unto thee, in thy mouth, and in thy heart, that thou mayest do it.

– Deuteronomy 30: 10 – 14

Moses, in his final farewell address to the children of Israel, does not even hint at any sense of moral pessimism or despair, which would have been the case had he, as the great lawgiver, subscribed to the doctrine of Original Sin. So, if Moses himself did not subscribe to this doctrine, we can reasonably conclude that it does not form a part of Jewish doctrine either. The whole positive and upbeat spirit of Moses’ final address is summed up in the final words: that thou mayest do it.

Contrast this with Paul’s creative doctoring of Moses’ famous farewell address as it appears in the tenth chapter of his Epistle to the Romans:

For Moses describeth the righteousness which is of the law, that the man that doeth those things shall live by them. But the righteousness which is of faith speaketh on this wise, Say not in thine heart, Who shall ascend into heaven? (that is, to bring Christ down from above:) Or, who shall descend into the deep? (that is, to bring up Christ again from the dead.) But what saith it? The word is nigh thee, even in thy mouth, and in thy heart: that is, the word of faith, which we preach.

– Romans 10: 5 – 8

Most who read and compare these two passages, one from the Old Testament, and the other from the New Testament, will see the thematic correspondences and similarities that Paul has written into his Epistle to the Romans. The imagery of going up into heaven is common to both passages, and instead of across the sea, Paul uses the imagery of descending down into the deep. But the crucial difference is in the respective endings of both passages – that is, their final verses. Gone are the crucial words, that thou mayest do it, from Paul’s Epistle to the Romans; in its place is: that is, the word of faith, which we preach. That Paul would doctor and mutilate the final farewell address of the great lawgiver Moses in his Epistle to the Romans would strike many Orthodox Jews as a blatant sacrilege and affront to Judaism. No wonder, they say, that Paul was much more successful ministering to the gentiles than he was to the Jews; the Jews knew better, and would not fall for Paul’s blatant revisionism.

In the preceding verses, Paul expresses his wishes that the nation of Israel might be saved – that is, according to his understanding of salvation as being submission to the saving grace of Christ, which Paul sees as the end of the Law. In their ignorance, Paul believes, the Jews have set up their own righteousness instead of the righteousness of God, which he sees as submission to Christ. But Jews, being the staunch pure, pristine monotheists that they are, see the worship of anything or anyone other than the invisible, incorporeal God the Father, or God the Absolute as being blasphemy and idolatry, and a violation of the first two commandments. When it comes to Mrs. Nagata’s native Buddhism, the analogy is that Judaism would fall more into the Jiriki camp, or those who believe in salvation via their own power and effort, whereas Christianity would definitely fall into the Tariki camp – that is, salvation through the saving grace and power of another, which would be a divine Bodhisattva in Buddhism, and Jesus Christ in Christianity. And in the preceding two chapters of Romans, Paul makes his core case for what he sees as the absolute futility of trying to save oneself.

We know that the original Jerusalem Church of James the Just, the brother of Jesus, which carried on Jesus’ teachings immediately after his crucifixion, was thoroughly Jewish and Torah abiding in its basic spiritual orientation – that would put them firmly into the Jiriki camp of Judaism. The Jerusalem Church was merely continuing the spiritual teachings and legacy of their martyred founder, Jesus of Nazareth. It was Paul who came along later and devised his own theology of Jesus and salvation through faith alone, and not from works done in accordance with the Law of Moses. And we know, through what Luke wrote in the fifteenth and twenty first to twenty third chapters of the Book of Acts, that Paul and his teachings were radically at odds with those of the Jerusalem Church. According to Paul, Jesus Christ was the second Adam, who reversed the fall of man brought about by the first Adam:

Wherefore, as by one man sin entered into the world, and death by sin; and so death passed upon all men, for that all have sinned.

– Romans 5: 12

That one man who introduced sin into the world is, of course, Adam, and, according to Paul, Adam’s original sin of eating the forbidden fruit with his partner Eve allowed sin and death to be passed on to all men. From this Bible verse, we may reasonably conclude that Paul was the original conceiver of the doctrine of Original Sin. In the preceding verses, Paul speaks of the atonement that the transformational passion of Jesus Christ in his crucifixion and resurrection brings to those who believe in it.

There is yet a more cynical view of the doctrine of Original Sin and its origins, which goes like this: The crucifixion of Jesus was a totally unexpected and tragic event; previous to it, Jesus’ disciples fully expected to be his partners and co-administrators in the running of his Messianic Kingdom. This was a huge setback that really knocked Jesus’ followers for a loop, and sent them back to the drawing board to try to devise some kind of explanation for why God allowed this to happen. The basic solution that Paul and his followers came up with was based on the doctrine of Original Sin, which they saw as being the primal and universal spiritual malady of all mankind, and that Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection atoned for this Original Sin, to reconcile all those who believe in it back to God and the Kingdom of Heaven, which was not an earthly kingdom, but a heavenly one. To put things another way, Christianity prescribed belief in Jesus’ sacrificial death and atonement as the universal, sovereign remedy for the malady of Original Sin; Jews saw no need for the remedy, since they did not see themselves as suffering from the original malady either.

Can Sin Be Inherited?

Although Paul had a vague notion that somehow, sin entered the world through Adam, he was unclear as to exactly how that Original Sin was transmitted to the mass of humanity. Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 AD) maintained that, through concupiscence, or hurtful desire, transmitted via libido and the sexual act, Adam and Eve recreated their fallen human nature through procreation, and passed on their Original Sin to future generations. – 1. Libido and sexual desire may have had a normal and healthy place within the scheme of human affections prior to the fall, said Augustine, but all of this was corrupted by Original Sin. Through Augustine, sin became something that was highly clinical, almost genetic in nature; however, as far as modern scientists have mapped out the human genome, they have yet to isolate the Original Sin gene. “For all have sinned, and have fallen short of the glory of God,” wrote Paul in his Epistle to the Romans, and if we revert to the original definition of sin as missing the mark, or hamartia, then error and wrongdoing would also fall under the scope of our definition of sin. The question is: Can sin, or error, be transmitted from one generation to the next?

I had an interesting experience one evening in a supermarket that seemed to me to indicate that, indeed, this may be so. I saw three generations of the same family – the grandmother, the mother, and the little children, even down to an infant, all huddled around the same shopping cart. What I immediately noticed that all family members shared were the common facial features of a sickly, ashen grey complexion, with prominent bands of black, purple and green stripes or discolorations underneath their eyes – even down to the little infant. What on earth could have given every family member those same pathological markings and discolorations on their faces? My wonder and amazement vanished when I looked into their shopping cart and saw it filled with worthless, devitalized junk food. Even though the markings on their faces weren’t the result of any inherited genetic traits, it was clear that the identical poor eating habits were being passed on faithfully from one generation to the next, just as surely as if by some gene.

Psychologists and adherents of alcoholics anonymous and other twelve step programs know that dysfunctional behavioral patterns are faithfully transmitted in families, from one generation to the next, often with alarming precision and accuracy. This often seems to happen as a weird pathological perversion of the Golden Rule in that the wrongdoing one received at the hands of one’s parents is then transmitted on to one’s children – with alarming faithfulness and accuracy, and often in spite of oneself. It is very hard indeed to break the multi-generational cycle of abuse begetting abuse. If one reflects on things a bit, one begins to see that so much of our behavior is an automatic, knee jerk reflex of cause and effect, with free will playing a much more limited role than most people assume. Too much of the time, we’re simply on automatic pilot. “For all have sinned, and fallen short of the glory of God.” Many have maintained that the dysfunctional family is now the norm, with truly healthy families being the exception rather than the rule. So maybe Augustine wasn’t that far off the mark in his observations and conclusions.

But what does the Bible have to say about Original Sin? Of course, we would be able to find references to the basic concept, especially in the epistles of Paul, but what about the Old Testament? Conservative Christians would be quick to trot out a particular “proof text” from the Book of Psalms:

Behold, I was shapen in iniquity; and in sin did my mother conceive me.

– Psalms 51: 5

But heck – there are a total of a hundred and fifty Psalms in the Book of Psalms, of every kind of devotional mood imaginable, from the very positive and upbeat to the very dejected and gloomy, like the fifty-first Psalm. In this Psalm, King David, who was not perfect by any means, prays for forgiveness of his sins. In addition to this “proof text” for Original Sin, there are other well-known gems from the other lines of this Psalm. For the herbalist and natural healer, there is the line: Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean: (verse 7). But most importantly, there are the following verses, later on:

For thou desirest not sacrifice; else I would give it: thou delightest not in burnt offering. The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.

– Psalms 51: 16 – 17

These verses are interesting because they weigh in against what many conservative Christians maintain about Old Testament Judaism: that blood sacrifice was absolutely necessary for the remission of sins. It is against this backdrop of the presumed absolute necessity of blood sacrifice that they maintain that Jesus Christ offered up the perfect blood sacrifice for all time upon the cross at Calvary, thus rendering all further blood sacrifice unnecessary and obsolete. But these two verses seem to cut that doctrine off at the knees, so to speak, or at least offer a viable alternative to blood sacrifice.

But seriously – can sin be transmitted from one generation to the next? Although Psalms 51: 5 suggests that it can, Jewish rabbis are quick to point out, in refuting the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, that there are other parts of the Old Testament that definitely weigh in against the idea that sin can be transmitted from one generation to the next. Consider the following:

The word of the Lord came to me again, saying, What mean ye, that ye use this proverb concerning the land of Israel, saying, The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge? As I live, said the Lord God, ye shall not have occasion any more to use this proverb in Israel.

– Ezekiel 18: 1 – 3

From the imagery used here, it is clear that the God of Israel is plainly refuting the notion that the karmic chain of cause and effect can be automatically transmitted from one generation to the next. In fact, Jewish rabbis are quick to point out that the whole eighteenth chapter of Ezekiel is a refutation by God of the Christian doctrine of Original Sin, and that the sins of one person can be inherited or transmitted from one person or generation to another. In the verses that follow, God gives numerous concrete examples to illustrate His point, but the whole crux or gist of the matter is stated in the following verses:

The soul that sinneth, it shall die. The son shall not bear the iniquity of the father, neither shall the father bear the iniquity of the son: the righteousness of the righteous shall be upon him, and the wickedness of the wicked shall be upon him. But if the wicked will turn from all his sins that he hath committed, and keep all my statutes, and do that which is lawful and right, he shall surely live, he shall not die. All his transgressions that he hath committed, they shall not be mentioned unto him: in his righteousness that he hath done he shall live. Have I any pleasure at all that the wicked should die? saith the Lord God: and not that he should return from his ways, and live?

– Ezekiel 18: 20 – 23

From the above verses, God affirms that one person cannot bear the sins of another, and thereby upholds the spiritual principle of personal responsibility for one’s own deeds and actions. We also learn that God desires repentance, and is not vindictive; in other words, He takes no pleasure in punishment, and desires that all should repent of their sins, and live. These four short verses alone offer one big “dis-proof text” to counter and rebuke so much of core Christian doctrine, especially in its more conservative and fundamentalist forms. We are not “sinners in the hands of an angry God”. Hallelujah! And the whole eighteenth chapter of Ezekiel backs up and reinforces what is said in these verses.

Yes, you might say, but how do I reconcile this with Psalms 51: 5? Lo and behold – it is possible to find verses and passages in the Bible that contradict each other – not just in trivial details, but in core matters of doctrine as well. Take the Book of Psalms, for example – it is a veritable smorgasbord of hymns written from devotional moods and perspectives that can be as different as night and day. Scriptural myopia, I call it – not being able to see the biblical forest for the trees. Sure, the Bible may throw out all sorts of things, but what do the elders of the church or synagogue say – how have they decided these matters, and what do they think is crucial? This brings me to another important point – that Scripture alone is not the sole guide and authority in deciding doctrinal matters, even for Christian sects and denominations that insist that it is. And the truth that different passages of Scripture can give conflicting views and opinions on spiritual matters should be amply demonstrated by the passages I have cited. So, we turn to the elders of the church or synagogue for their guidance – and it just so happens that Judaism takes a more optimistic, upbeat position on these questions, whereas Christianity comes down on the side of moral pessimism.

Or, you can weigh the evidence, both pro and con. And what we have seen is that there is just one verse from the fifty-first Psalm that weighs in on the side of Original Sin, as opposed to a whole chapter in the Book of Ezekiel that weighs in against it. That makes Ezekiel 18 the winner! One must also remember that there is a particularly robust and vigorous tradition of spiritual discussion and debate within Judaism. The old joke goes that if you ask three different Jewish rabbis the same question, it is guaranteed that you will get at least four different answers. The Christian tradition, by contrast, has not been so open and accepting of discussion and debate, and more rigid and dogmatic in its doctrinal stances on many different things. There are many different reasons for this that I will not go into here, but that’s the way it is.

The Malady of the Fall – And Its Cure

The two core doctrines that lie at the very heart of Christianity are Original Sin, which led to the fall of man, and Jesus Christ’s atonement on the cross at Calvary. The two are very intimately intertwined, fitting together like a hand and glove, with Original Sin being the universal malady, and Christ’s atonement the cure. Now, any good doctor knows that, in order to prescribe the right remedy, or cure, you have to have a clear and accurate assessment of the malady and its nature. Basically, all major sects and denominations of Christianity today are in agreement that, because of the Original Sin of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, sin entered the world, and mankind now exists in a fallen state, in need of the redemption offered by Jesus Christ. But not all of these sects and denominations are in agreement as to what the exact nature of that fallen state is; therefore, their understanding of the remedy offered by Christ’s atonement also differs.

The main dividing line here regarding different views of what exactly man’s fallen state is lies between Eastern and Western Christianity – that is, between the Eastern Orthodox Church and Western Christianity in its various forms, both Catholic and Protestant. Simply speaking, Western Christianity sees Original Sin, and man’s fallen state in legal or transactional terms, as a debt that needs to be paid to God. Eastern Christianity, on the other hand, sees man’s fallen state as an estrangement from God, as an inner woundedness that needs healing; in other words, the remedy in Eastern Christianity is to be reaccepted and reintegrated back into the Kingdom of God, with the church being seen as a hospital for ailing souls. The legalistic or transactional way of looking at sin and salvation was introduced into Western Christianity in the eleventh century AD by Anselm of Canterbury, via his theological treatise Cur Deus Homo, or Why God Became Man. – 2. This transactional view of sin and salvation led to horrible abuses by the Catholic Church in the late Middle Ages, such as the buying and selling of indulgences, which was one of the big things that brought about the Protestant Reformation. Eastern Christianity never bought into these ideas, so there were no abuses to reform.

Earlier on in this article, I introduced you to biblical evidence from the Old Testament, or the Jewish Scriptures, that called the whole Christian doctrine of Original Sin into question. In this section, I have endeavored to show you that, even within the Christian theological paradigm, there are more positive and life affirming perspectives on Original Sin and the nature of man’s fallen state, versus more negative ones. In this article, I want to limit myself only to Original Sin, and the nature of man’s fallen state; I will address Christian perspectives on atonement and salvation in a future article.

The Original Sin Wars: Augustine versus Pelagius

The Original Sin Wars: Augustine versus Pelagius

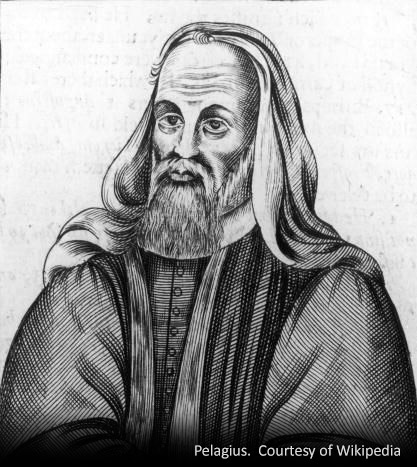

In Christianity today, at least in its mainstream sects and denominations, the doctrine of Original Sin reigns supreme in defining the conventional Christian perspective on human nature. As we have seen, Paul had a rudimentary version of the doctrine, which was later refined and put into its final form by Augustine of Hippo, who was generally acknowledged to be the leading Christian theologian of his day, and a towering intellect. But Augustine’s views on Original Sin did not go unchallenged; a doctrine that paints such a gloomy and negative picture of human nature was bound to have those who offered dissenting opinions. The chief opponent who refuted Augustine’s doctrine of Original Sin was the English cleric and moralist, Pelagius. With his dissent to Augustine’s doctrine of Original Sin, Pelagius ignited a fierce debate over its pros and cons – a debate that has come to be called the Pelagian Controversy. For those who are loyal and conservative members of the church, the word “controversy” seems to be too mild – they prefer to call it a full-blown heresy.

Not surprisingly, Pelagius harkened back to the Old Testament, to the Torah, to be exact, to root his views in an unequivocal “disproof text” against the doctrine of Original Sin:

Parents are not to be put to death for their children, nor children put to death for their parents; each will die for their own sin.

– Deuteronomy 24: 16

Sounds a lot like the passage from Ezekiel that we quoted earlier, doesn’t it? Ezekiel was just echoing and reaffirming the spiritual principles laid out in the above verse from Deuteronomy. At least Judaism is consistent in its affirmation of the spiritual laws of free will and personal responsibility for one’s own actions and choices. You might say that, in the essential spirit of his message, Pelagius was reverting back to the old Judaic position on human nature, which is, after all, part of the larger Judeo-Christian tradition.

In asserting the inherent morality and free will of man to choose good over evil and not sin, Pelagius was not denying the role of the saving grace of God and Christ to facilitate the turning of man towards the good. According to Pelagius, God’s first bestowal of grace upon man was the gift of free will, followed by the Law of Moses, and then the teachings of Jesus. These would enable a person to perceive the right and moral course of action and follow it. Pelagius felt that Augustine, in devising his doctrine of Original Sin, was overly influenced by his Manichaean past, was elevating evil to the same status and power as God, and was succumbing to a defeatist attitude of pagan fatalism and putting it forth as Christian doctrine. Divine help is always standing by to assist us in doing the good, and God never puts forth any commandments, nor asks us to do anything that is beyond our capabilities, according to Pelagius. – 3.

Although conservative Christians consider church doctrine to be sacrosanct, and handed down directly from God, the truth is that all Christian doctrine was either inherited or passed down from the Jewish tradition, or was the product of human beings, with their own inherent personalities, as well as character flaws and weaknesses. So, in addition to studying the doctrines themselves, we should also study the lives and personal backgrounds of those who devised the doctrines – and for Original Sin, that would be Augustine. Not that much is known with certainty about the apostle Paul, who laid the doctrine out in its rudimentary form, aside from what the Book of Acts and the Pauline epistles reveal about him, but a lot more is known about Augustine of Hippo. Previous to Christianity, Augustine was an adherent of Manichaeism, a religious sect that is often seen as an offshoot of Gnosticism, which posits a radical dualism between God and the Spirit, which are seen as being pure and good, and the flesh, which is seen as being evil and sinful. As a young man, Augustine confessed that he had been a lusty debaucher, and unable to control his wild passions and desires. Augustine famously said, “I cannot not sin!”

What finally decided the outcome of the Pelagian Controversy turned out to be more a matter of religious politics than anything else. Augustine and his supporters were way more powerful and influential in the early church than Pelagius. At the behest of Augustine, a church council was convened at Carthage in 418 AD which declared Pelagius’ views to be heretical. – 3. And with this fateful decision, Christianity lost the golden opportunity it had for introducing another perspective on human nature that would have tempered and moderated the harshness of Original Sin, leading, perhaps, to a Christian theology that was kinder and more humane. Others have said that without the doctrine of Original Sin, the saving grace of Christ, and his atonement on the cross at Calvary would be rendered unnecessary, or at least marginalized to a position of auxiliary or secondary importance. Politically speaking, this would have diminished the power and position of the Christian priesthood considerably – and maybe that’s the real reason why Pelagianism had to be defeated.

Conclusion: Original Sin is a Highly Personal Matter

In conclusion, to me, the doctrine of Original Sin is kind of like the old Chinese Taoist Yin / Yang symbol, encompassing both a bright, positive side as well as a dark, negative side. I would like to leave you with a couple of short anecdotes, one illustrating the bright side of Original Sin, and the other its dark side.

On a late night train ride in Romania, I found myself sharing my train compartment with a bunch of Christian missionaries. Somehow, I got locked into a tiresome, almost endless argument with a guy who seemed to be the head of the missionary group about Original Sin. Tired and weary, I got home to my Bucharest apartment in the wee hours of the morning, right before sunrise, totally drained and exhausted. Nevertheless, I mustered up the energy to consult the Chinese Oracle, the I Ching, to ask it the crucial question, “What is the positive value of the doctrine of Original Sin?” The I Ching’s answer was very simple and direct: I got Hexagram Fifteen, titled Modesty, unchanging. In other words, what the I Ching was saying, in no uncertain terms, was that the positive value of the doctrine of Original Sin lay in its ability to keep those who believe in it humble and modest, and always aware of their potential for sin and error.

The second anecdote goes as follows:

One fine afternoon in August, I was strolling on a beach on the Black Sea coast in Romania when I spotted an informal gathering of young people; I struck up a conversation with two of them, a young man and his female partner. At that time, in the early 90’s, not long after the fall of communism, Romania was struggling to catch up with the more advanced nations of Western Europe. I told them the story of the televangelist Jimmy Swaggart, of how he got caught red handed with prostitutes, and of his tearful, “My Lord, I have sinned against you!” confession on national TV. After listening to my story, the young man looked at me with his jaw dropped in an expression of absolute incredulity. After what seemed like the longest time, he finally said to me, in Romanian, “But I thought that America was an advanced nation!”

Definitely, the antics of American televangelists can seem to be pretty crazy, childish and bizarre to those encountering them for the first time. Most of them come from a conservative Protestant or Calvinist background that insists that man, in his fallen state, is totally depraved. And that same conservative Protestant religious background that they were brought up in also views men, and women, as sinners in the hands of an angry God. Aren’t these wayward televangelists merely acting out their worst fears about what they see as their own depraved moral nature in the scandals that seem to follow them around like their own shadow? The old joke about fundamentalist “fire and brimstone” preachers is that you can tell what they’re doing behind closed doors by the sins that they are ranting against from the pulpit. Enter Elmer Gantry, the wayward preacher character created by Sinclair Lewis in his satirical novel of the same name, who is now an icon of American popular culture and folklore. A study of the personal lives of wayward televangelists can provide one with an interesting character study of the negative effects of the doctrine of Original Sin. The other main negative effect of the doctrine of Original Sin, besides this scandalous acting out of total depravity, is the terrible way that it has stunted and maimed so much human potential.

But casting aside these extremes, I would like to say in conclusion that how one feels about the doctrine of Original Sin, and what place it occupies within one’s own regime of moral belief and behavior, is a highly personal matter. Some people may feel themselves to be irredeemably evil and wicked, and desperately in need of this doctrine in order to straighten up and fly right. To them, the old saying, “Read the Bible – it’ll scare the hell out of you!” may be spot on. Others, who are more inherently virtuous by nature and temperament, may be more inclined to do the right and virtuous thing on its own merits, believing that virtue is its own reward. I believe that the two early church fathers who squared off in the epic debate over Original Sin – Augustine and Pelagius – were emblematic of the former and the latter type of person, respectively. Then there are those who are caught somewhere in the middle, in between these two extremes, who have yet to sort out exactly where they stand – and exactly what their own nature is – regarding crucial matters of sin and virtue. In conclusion, I do not want to pontificate to others about the thorny, personal matter of Original Sin; each individual must figure that out for themselves.

***

Sources: