Those who are searching for the pure teachings of Christianity may be searching in vain, because Christianity is actually a hybrid religion, born from the fusion or marriage of the Judaic and the Hellenistic streams of religion and spirituality. This article gives evidence and proof of this hybridization, and gives a brief synopsis of how this intermarriage happened.

Introduction: What Is Christianity, Really?

Too many Christians nowadays, perhaps the vast majority of them, are woefully ignorant of the true nature and origins of the Christian religion. And the more fervently they believe, it seems, the more in the dark they are about these matters. Most Christian believers just naturally assume that it was the natural next step for the God of Israel to send His only begotten Son to earth to be crucified as atonement for the sins of humanity, and don’t even think twice about it. There are also Christian fundamentalists who scour their Bibles, seeking to get back to the pure teachings of Christianity; sadly, their efforts are ultimately doomed to failure, because what they are seeking is actually an illusion. The truth is that Christianity is, in fact, a hybrid religion, born of the fusion or intermingling of the Judaic and the Hellenistic streams of religion and spirituality. If one draws an analogy to genetics in this hybridization process, Judaism contributed the dominant genes, whereas Hellenistic religion and spirituality contributed the recessive genes. In other words, what is most readily apparent from a superficial appraisal of the Christian religion is its Jewish roots; the Hellenistic contribution is not so readily apparent to the casual observer, but it is definitely there, as I will prove in this article.

Exhibit A: Judaism versus Christianity on Theology and Doctrine

In many ways, Christianity tries very hard to prove how Jewish it is. Christian apologists have scoured the Old Testament, looking for prophetic passages that seem to presage the advent of Jesus Christ as the new world savior; Jewish rabbis counter that many of these so-called prophetic passages are twisted or taken out of context. Similarly, Christian apologists are eager to tout the Pharisaic credentials of the apostle Paul, whereas Jewish rabbis are extremely dubious and skeptical of these claims, for several reasons. Could these tireless efforts on the part of Christianity be part of a compensatory cover up of some deeper, hidden truth – like the non-Jewish Greek or Hellenistic elements in Christianity? Perhaps the most powerful piece of evidence that indicates that Christianity is not purely Jewish in its heritage and origins is the huge differences between Judaism and Christianity on core matters of theology and doctrine. These differences are so great that many Jews during the Spanish Inquisition were tortured and died for their faith rather than convert to Christianity. These core differences are as follows:

The Nature of God: The spiritual heritage of Judaism is absolute, pure, pristine monotheism. In other words, Jews believe that God is an absolute Unity, whereas Christians believe in a triune Godhead, or Holy Trinity – or one God in three persons. However, three-in-one isn’t quite the same as One – period, or One without a second. Nevertheless, most Christians have been so indoctrinated in Trinitarian theology that they may be blind to this difference, believing that there is essentially no difference between One and three-in-one. Trinities, or groupings of three gods, or goddesses, were actually quite common in Greco-Roman paganism, however.

The Divinity of Jesus Christ: Jews take a strict, literal interpretation of the first two commandments, which forbid idolatry, or the worship of anyone or anything else besides the God of Israel, who Jesus affectionately called Abba, or the Father, as being divine. Christianity, on the other hand, has raised Jesus to divine status as the second person of the Holy Trinity, regarding him to be fully coexistent and coeternal with God the Father. The great virtue of the absolute monotheism of Judaism is that it keeps the boundaries between God and man clear and distinct, and does not confuse the two. The Christian Jesus, on the other hand, was at once fully God and fully man, being born of a virgin and conceived by the Holy Spirit, or the third person of the Christian Trinity. Where do we find stories of other demigods, or those whose birth or origins were half human and half divine? We find them in Greek mythology.

The Messiah: There is a vast difference between the Jewish and Christian conceptions of who, or what, the Messiah is supposed to be. To the Jews, the Messiah is supposed to be a divinely anointed – but not divine himself – priest / king and national deliverer for the state of Israel, who would drive out the foreign occupiers and re-establish home rule for the Jews, thereby ushering in the Messianic Age, in which Israel would act as a spiritual beacon for the nations. Because Jesus was not successful in doing this, Judaism sees Jesus as another failed Messiah. At his trial in the Christian gospels, Jesus Christ plainly tells Pontius Pilate that his kingdom is not of this world; and so, Christianity sees Jesus’ messiahship as being that of a divine deliverer of all mankind from the universal enemies of sin and death. In other words, the Hellenizers of the Christian message wanted to take Jesus’ role as a deliverer beyond the narrow confines of Judaism into a realm that had spiritual relevance for all, both Jew and Gentile alike. The old Greco-Roman Mystery Religions that preceded Christianity promised spiritual deliverance and a favorable position in the afterlife to those who worshiped and identified with a savior deity in his transformational passion or sacrifice. Sound familiar? It definitely should.

Sin and Human Nature: Amazingly enough, although there is the story of Adam and Eve in the Jewish Bible, which is essentially the same as the Christian Old Testament, Jews don’t draw the same lesson of Original Sin from it as Christians do. In general, the Jewish spiritual tradition is a lot more positive and upbeat about human nature than Christianity has been, seeing the human being as being free to choose between the evil impulse and the good one. By following the Law of Moses, a Jew could gradually cultivate the good impulse within themselves, and strengthen their spiritual muscles, so to speak. Paul, on the other hand, writes that he is a hopeless slave to sin in his epistles, such as the seventh and eighth chapters of his Epistle to the Romans, and is totally powerless to save himself without the divine saving grace of Jesus Christ. If Paul, the supposed Jewish Pharisee, did not get his pessimistic spiritual attitude from Judaism, where did he get it? Certain of the old Greco-Roman mystery religions, such as Orphism, also had a very negative or pessimistic view of sin and the flesh, regarding the body as a tomb for the Soul. – 1.

Moral Choice and Free Will: In Christianity, there is talk of God giving man free will, but certain elements of Christian doctrine really don’t favor this position. Paul, in his epistles, talks about being “in Christ”, and the very semantics of this phrase suggest an abdication of free will, that the one who is “in Christ” really doesn’t belong to oneself, but belongs to another. Judaism, on the other hand, in keeping with its more optimistic and upbeat stance on human nature, also favors the use and exercise of our God given free will much more than Christianity does. Indeed, the philosophical debate between predestination and free will has been going on since time immemorial, with moral pessimists favoring the former and moral optimists the latter.

Blood Sacrifice and the Eucharist: Christians maintain that, at the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, blood sacrifice was absolutely essential for remission of one’s sins; then, Jesus Christ came along and underwent the ultimate human blood sacrifice for our sins, rendering all further sacrifice unnecessary. Jewish rabbis counter that, even in Old Testament Judaism, blood sacrifice wasn’t the only way to repent and atone for one’s sins:

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.

– Psalms 51:17

Yet, Christian apologists persist in insisting that blood sacrifice was an absolute necessity in Old Testament Judaism, even to the point of taking certain Bible verses out of context to prove their point, like Leviticus 17:11, about the life of the flesh being in the blood. Jewish rabbis counter that they are taking this passage way out of context; the seventeenth chapter of Leviticus deals with the dietary laws, and all this passage is saying is that you must drain all the blood out of meat before eating it. Indeed, the very idea of drinking blood, either literal or symbolic, is an abhorrent abomination to all Jews, but in the Christian Eucharist, worshipers symbolically eat the body and drink the blood of Jesus. Here again, the apostle Paul was our first Christian writer on the subject of the Eucharist (1 Corinthians 11: 23 – 29). Where did Paul get this? Paul was from the city of Tarsus in Cilicia, which was, at the time, a big center for the cult of Mithras, -2. which featured a Eucharistic meal very similar to the Christian one. Another ritual of the Mithraic cult was the Taurobolium, in which the devotee bathed in the blood of a sacrificed bull. To Jews, all this blood and gore stuff reeked of primitive paganism and human sacrifice, which they considered to be an abomination.

Exhibit B: Paul and the Jerusalem Church

Many, if not most, Christians know that Jesus was a Jewish carpenter and an itinerant rabbi from Galilee. Immediately after the crucifixion, a small band of Jesus’ disciples, led by his brother James, carried on his teachings in his memory; the church, or synagogue if you will, was located in Jerusalem, and was called the Jerusalem Church. This was the original Jesus movement, and it was thoroughly Jewish in its spiritual orientation and practices; the original members of the Jerusalem Church were Torah observant, and considered themselves to be another sect of Judaism, dedicated to the spiritual renewal of their faith through the memory and teachings of their martyred founder, Jesus of Nazareth. Besides James, other disciples, such as Peter and John, were also at the helm of this organization. Then along came Paul, who had different ideas, and a different vision of where the Jesus movement should go; but in the beginning, he was a member, considering himself to be the apostle to the Gentiles, with the others being the apostles to the Jews, or to the circumcision, as he put it. Just read chapter fifteen of Acts.

The main event or milestone in the fifteenth chapter of the Book of Acts is the first church council, which was convened in Jerusalem around the year 50 AD by James, whom both Luke and Paul designate as the brother of the Lord Jesus. The main issue to be discussed was whether gentile converts to Christianity had to be circumcised, follow the dietary laws, and abide by all the other Laws of Moses. Paul, of course, argues that gentile converts don’t need to be circumcised or follow the Mosaic Law. In the end, James relents and prescribes a very limited set of laws and regulations that gentile converts had to follow: abstain from pollutions of idols, from fornication, from things strangled, and from blood. So here, Paul seems to have won the day against the Jewish hardliners of the sect, who demanded total obedience to the Law. In the 21st chapter, things get a bit more serious; Paul returns to Jerusalem, in spite of being warned not to go. When he gets there, James takes Paul aside and tells him that he has heard reports that he has been teaching Jews who were living among the gentiles to forsake the Law of Moses, not to circumcise their children, and not to walk after the Jewish customs. James orders Paul to undergo a seven day purification ritual with four other wayward disciples in order to prove his allegiance to the Law of Moses, which Paul does.

At the end of the purification ritual, Paul and the others go to the Jerusalem Temple to make an offering. While there, Paul is recognized by some Jews from Asia who point out to the crowd that Paul has been teaching against the Law, the Jewish people, and against the holy temple; Paul is also accused of desecrating the Jerusalem Temple by bringing a Greek man into it. A murderous mob immediately gathers around Paul, but before they can kill him, the police come to save him. In chapter 22, Paul makes his case and gives his defense, telling the story of his conversion to being a follower of Jesus. In chapter 23, Paul is hauled before a religious tribunal and asked to make his case; there is also a group of assassins that forms, swearing not to eat nor drink until they have killed Paul. Paul finally reveals that he is a Roman citizen, and is escorted under armed guard to the Roman port city of Caesarea in order to escape the violence and the threats upon his life.

One must remember that Luke’s overall editorial agenda in the Book of Acts was to portray Paul as a great hero and missionary to the gentiles. But even so, Luke could not avoid mentioning these scandalous and unsavory incidents and run-ins that Paul had with the Jerusalem Church and its leadership – and with other pious Jews in Jerusalem who had also heard scandalous rumors about Paul’s wayward preaching. Obviously, what Paul was preaching among the gentiles, and to the Jews that he found among them, wasn’t exactly kosher – and wasn’t exactly Judaism either, it seems. In the second chapter of his Epistle to the Galatians, Paul’s own tone is considerably more haughty and defiant towards the leadership of the Jerusalem Church; he resents the intrusion of its snooping agents as robbing him of the freedom he has in Christ. From what he says in this epistle, we can infer that Paul definitely does not submit to their authority, as he writes that who or what they were mattered little to him. It seems as if Paul felt that he had to spend a certain amount of time within the ranks of the Jerusalem Church in order to establish his basic connections with the original Jesus movement to enhance his credibility among his gentile followers, but after that, he split with them to start his own gentile version of Christianity.

The Jerusalem Church, being thoroughly Jewish in its spiritual orientation, was zealous for the Law of Moses; it revered their founder, Jesus of Nazareth, as a great prophet and spiritual teacher, but did not consider him to be divine. The idea that Jesus was divine was apparently started by the apostle Paul, who cast Jesus in the role of a dying and rising savior deity after the fashion of the old Greco-Roman mystery religions. Present day Christians see in Paul the first true Christian, but this might just be an exercise in circular reasoning, because it was Paul who first laid the basic doctrinal groundwork for the religion that came to be known as Christianity. If Paul with his gentile version of Christianity had not come along when it did, the Jerusalem Church could well have remained just another sect of Judaism, perhaps perishing altogether with the Roman holocaust of Judea and the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple. And so, we have Paul and his followers to thank for the establishment of Christianity, which has now become the most populous religion on earth.

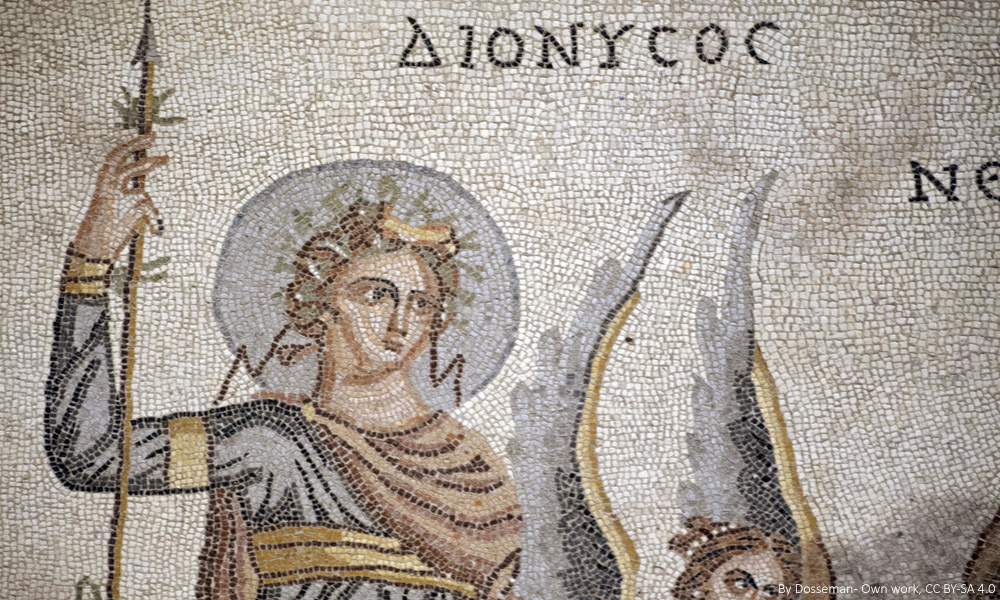

Exhibit C: Dionysian Overtones in Acts and the Gospels

In the first telling of Paul’s conversion experience on the road to Damascus in the Book of Acts, there is a curious phrase that appears. I quote here from the King James Version of the Bible:

And he said, Who art thou, Lord? And the Lord said, I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks.

– Acts 9: 5

If you have a King James Version of the Bible, you will find that phrase, “it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks” in your Bible for that verse; if you don’t have a King James Version of the Bible, chances are that you won’t be able to find it. The truth is that this particular phrase, “it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks” has been dropped from most translations of the Bible because it carries too much pagan baggage. And the phrase really contributes nothing to the overall story line anyway. This phrase would have been quite familiar back in the days when Luke first wrote it, because it is a line from a play by Euripides, The Bacchae, which is about the Greek god Dionysus, known to the Romans as Bacchus, who was the god of wine and religious ecstasy. And yes, Dionysus was one of the dying and rising savior gods of the old Greco-Roman mystery religions – and a pretty big one at that, judging from all the references and allusions there are to him in the Christian gospels. “It is hard for thee to kick against the pricks” draws an allusion to the process of plowing, in which, if the ox resists the plowman, the pricks or goads are only driven in deeper into his flesh, thereby hurting the ox. The message here is that, for Paul, resistance to the risen Christ is futile, since Jesus is divine, and he is but a mere mortal. The original line from Euripides’ The Bacchae, in which this phrase appears, is as follows:

“Better to yield him prayer and sacrifice than to kick against the pricks, since Dionyse is god, and thou but mortal.” – Dionysus in The Bacchae. – 3.

Perhaps the most obvious allusion to Dionysus in the Christian gospels is Jesus’ first miracle at the wedding at Cana, where he changes water into wine. Another obvious allusion to Dionysus is where Jesus tells his disciples that he is the true vine, and his disciples are the branches bearing fruit, which appears in the beginning of chapter fifteen of John’s gospel. But beyond these obvious references to grapes and wine, many of the personal characteristics of Jesus were those that he also shared with Dionysus, such as a tendency to associate with prostitutes, tax collectors, and others who were marginalized by society, as well as his remarks about how a prophet is seldom honored in his own country, which was a favorite line of Dionysus as well. The theme of a just man, wrongly accused before the law in a mock trial is also very Dionysian; in Euripides’ play, The Bacchae, Dionysus suffers in a mock trial before the King of Thebes. In the Christian gospels, Jesus suffers a similar fate when he is brought before Pontius Pilate. But in The Bacchae, Dionysus finally emerges victorious over his persecutors – and so does Jesus in his triumphant resurrection.

In Biblical interpretation or exegesis, there is a technique known as types or typology, in which certain figures from the Old Testament are said to be types that presage the advent of figures in the New Testament; for example, Joseph from the Old Testament is said to be a type that presages Jesus. Being eager to strengthen the connections and parallels between Judaism and Christianity in any way they can, Biblical exegetes are always quick to point out typological parallels between the Old Testament and the New, but this whole typology technique can also be applied to parallels between the New Testament Jesus and the dying and rising savior deities of the old Greco-Roman mystery religions that preceded it. And so, Dionysus is just one old savior deity that can be seen as a pagan type for Jesus; there are also others. Like Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine, Jesus performed many miraculous healings, for example. Psychological and historical research shows that people tend to be most conservative and resistant to change when it comes to their religion; after all, it’s only natural to be prudent and cautious when the fate of your eternal soul is at stake. Religious syncretism involves the appropriation or taking over of the various forms, myths and symbols of an older religion by a newer one, in order to facilitate the acceptance of the newer religion by the masses. And if Paul and his followers were to bring Christianity to the Greeks and Romans, or to a gentile audience, why not include a generous helping of the old myths, or sacred allegories, that this audience was brought up on?

Exhibit D: Hellenistic Influences in the Wisdom Literature and the Christian Apocrypha

Although the Judaic and the Hellenistic streams of religion and spirituality had their final fusion or integration in the Christian religion, this is a process that did not happen overnight; rather, it was years, even centuries, in the making. Many historical developments had to happen or take place before the Judaic and Hellenistic spiritual traditions, which were originally as different as night and day, were ready for their final fusion in the Christian religion. The Judaic tradition was insular, purist, and fiercely monotheistic in its original form, whereas the Hellenistic tradition was originally decidedly polytheistic; unlike the insular Judaic tradition, the Hellenistic tradition was also remarkably open, accepting and cosmopolitan in nature. How could this odd couple finally achieve a successful marriage? Although the story of how this happened is a complex one, the Hellenistic tradition had to evolve beyond the primitive polytheism that was its original state; through a process of prolonged philosophical reflection and inquiry, Hellenistic polytheism gradually evolved into a state of Monism, in which the classical philosophers of antiquity were finally able to accept the existence of a superior, transcendent single God of All, who was the ultimate Source of divinity behind all the lesser gods and goddesses. Although this statement could be called Christo-centric, Greek philosophy had evolved to the point where it could finally accept the sublime truth of the Christian gospels.

The Hellenistic era began with the conquests of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BCE, and ended with the fall of Rome some four centuries after Christ. Greek was the international lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean world, with Jews living in Palestine speaking Hebrew or Aramaic, and Jews living outside Palestine usually speaking Greek as their primary language. It has been said that there have been few civilizations in world history as enchanting and seductive as Greek or Hellenistic civilization, and it seems like no one, not even the Jews, was immune from its pervasive and far reaching influence. Although traditional Jewish religion and culture was very patriarchal in orientation, you have Wisdom being portrayed as a female figure, as a goddess who was the firstborn of God’s creation in the Old Testament Book of Proverbs. In the Christian Apocrypha, which can be found in between the Old and New Testaments in Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bibles, there is a book called the Wisdom of Solomon, which continues in the tradition of portraying Wisdom as a goddess. In the books of the Maccabees, which chronicle the Maccabean revolt against foreign Hellenistic overlords some 150 years before Christ, the origins of Christian notions of sin and substitutionary atonement can be seen, as evidenced by the following passage:

Because of them our enemies did not rule over our nation, the tyrant was punished, and the homeland purified – they having become, as it were, a ransom for the sin of our nation. And through the blood of those devout ones and their death as an expiation, Divine Providence preserved Israel that had previously been afflicted. – 4 Maccabees 17: 20 – 22

Since the Christian Apocrypha was written in the intertestamental period, or the period in between the Old and New Testaments, the Apocrypha fills us in on what was happening, and how Judaism was changing and opening up to Hellenistic influences, as well as resisting them, as in the Books of the Maccabees. The Books of the Maccabees are historical books that present valuable background material for understanding the Messianic fervor and expectations of Israel during the time of Jesus. Although Paul can be seen as the “point man” who finally brought about the merger or fusion of the Judaic and Hellenistic streams of religion and philosophy in the new world religion of Christianity, which he effectively founded, a lot of things were happening and things were moving in that general direction even before Paul made his appearance. If Paul had not come along when he did to accomplish this merger, sooner or later, someone else would have, I feel.

Conclusion: Hellenism Snuck in Through the Back Door

There’s actually nothing wrong with being a hybrid religion; in biology and genetics, there’s the phenomenon of hybrid vigor. Similarly, it helps if a great world religion, such as Christianity, arises from a religious, spiritual and philosophical foundation that is broad and robust. But we also have to take a look at the exact manner and circumstances under which this hybridization process took place, and in the case of Christianity, the methods that were used were deceptive and disingenuous in many ways. It seems like the masses of Christian believers have been told a certain story regarding the origins of their religion, when the actual truth of the matter was quite different. The single person who was most responsible for introducing Hellenistic elements and teachings into Christianity was Paul, assisted by his associate and protégé, Luke. Together, they essentially heisted and co-opted the Jewish Jesus movement and turned it into a totally new – and hybrid – world religion, which is Christianity.

Consider the following historical facts and circumstances:

Paul was born and raised in the city of Tarsus in the province of Cilicia, in what is now southern Turkey. Not only was Tarsus a big educational center in classical Greek philosophy, but it was also a big center for the pagan cult of Mithras, which was a Mystery Religion based on a solar savior deity who was born on December 25th; a Eucharistic meal that was quite similar to the one celebrated in the Christian mass was also a key ritual of Mithraism. Being exposed to pagan rituals celebrating the death and rebirth of pagan deities in his childhood, imagine Paul’s wonder and amazement in discovering that there were Jews who believed that their spiritual master, Jesus of Nazareth, had also died and risen from the dead. And this, of course, became the basis for Paul’s new gentile vision / version of Christianity.

Paul was never a personal disciple of Jesus, and had never met Jesus personally, in the flesh. This is highly atypical, perhaps even unique, in the history of world religions, which were usually started by disciples or apostles who had studied personally with their master.

Paul stakes all of his apostolic authority on a vision he had of the risen Christ while on the road to Damascus. The Book of Acts considers this to be such a crucial, watershed event in the early history of Christianity that it tells the story no less than three times. Yet, if you carefully read each one of the three tellings, there are significant differences among them, enough to cast doubt on the probable veracity of the event. Paul’s conversion story, as told in Acts, is nevertheless a great story, lending a lot of drama, gravitas and credibility to Paul’s claims.

Paul claims that he persecuted Christians before his conversion because he was a Pharisee. Yet, in the fifth chapter of Acts, the esteemed Pharisee Gamaliel, who was supposedly Paul’s own teacher, counsels a lenient “wait and see” approach when Peter, one of Jesus’ chief apostles, is brought to trial. So, were the Pharisees really opposed to the early Jesus movement, and did Jesus really have the conflicts with the Pharisees that he is portrayed as having in the Gospel of Matthew? Or was Paul under the employ of some other agent or authority, such as the High Priest in Jerusalem, who was a Sadducee, and not a Pharisee, when he was sent to Damascus? It must be remembered that the Sadducees were the main Jewish sect that collaborated with the Roman occupation of Judea, so Paul’s trip to Damascus to round up early Christians and bring them back for judgment may have been more of a political one than a religious one. There is the distinct possibility, now obscured by the shifting sands of time, that the early Jesus movement may also have been a movement of messianic national resistance to Rome.

In his First Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul says that he has become all things to all people, so that he might win some of them over to Christ (1 Corinthians 9: 19 – 23). This ability to become all things to all people is also a hallmark of the deceiver or con man. Paul says that he has done this in order to become a servant to all, but he may have also succumbed to the ethical fallacy of the ends justifies the means. If this is indeed the case, it’s not hard to see how Paul could have engaged in deceptive or disingenuous tactics in order to create the illusion of continuity or apostolic connection between himself and the gospel he was preaching on the one hand, and Jesus and the original Jewish Jesus movement on the other. On the one hand, you could say that Paul was really dedicated to the vision of Christ, and the gospel he was preaching, but on the other hand, you could also say that there was quite a bit of the opportunistic rogue in his overall personality and character. There’s definitely a lot more going on behind the scenes than Paul and his buddy Luke let on from the historical facts and circumstances presented above.

Okay, I’ve told you the negative or suspicious things about how Paul founded the new world religion known as Christianity – but what’s the positive side of things? First of all, there was an incredible amount of vision, dedication and spiritual work that went into Paul’s formulation of the doctrinal groundwork for Christianity. Even though there are some things that Jesus and his story, as presented in the Christian gospels, has in common with other pagan savior deities who preceded him, the blending of Hellenistic elements into the Christian spiritual tapestry wasn’t just a simple by-the-numbers job, or a cut and paste operation; Paul had to devise a religious, spiritual and metaphysical system that really worked and made sense to him and his followers. Paul mentions in his Epistle to the Galatians that he went away to Arabia shortly after his conversion experience, and this period of enforced spiritual solitude was probably necessary for him to fully digest and assimilate what his vision of the risen Christ meant, and to work out its myriad implications into a coherent system of religious doctrine and devotion. And once he had worked it all out, Paul became a tireless advocate and missionary for his new spiritual vision.

What we have today in Christianity is the religious and spiritual system that was laid out by Paul of Tarsus, for better or worse. Today, Christians go to the gospels to get the teachings of Jesus, and to the epistles of Paul for his teachings about Jesus, but the fact remains that the main interpreter of the life of Jesus and what it all meant for all the generations of Christians who came after him was Paul, who was our first Christian writer. Being our first Christian writer, everyone who followed Paul , including the writers of the four gospels, were heavily influenced by Paul’s vision of gentile Christianity, and his overall teachings and message. The gospels are not eyewitness accounts of the life of Jesus, but rather, they are theological memoirs of his life and teachings, compiled from various sources and the oral tradition some forty to seventy years after Jesus’ crucifixion. And so, we must always be circumspect, and keep in mind the tenuous nature of the connection between Jesus’ original teachings, whatever they might have been, and what has come down to us today via the Christian spiritual tradition. If really taken to heart, this realization should silence a lot of the dogmatic, extreme claims of Christian fundamentalists.

To get a broad overview of what Paul and his followers did in transforming the original Jewish Jesus movement into the hybrid religion of Christianity, the overall process was essentially one of transforming the original Jesus movement into a Mystery Religion after the old Hellenistic model. In other words, you could say that Christianity, as it has come down to us today, is basically the “mystery religionization” of Judaism, with Jesus of Nazareth, an itinerant preacher and rabbi from the Galilee, in its starring role as its central savior deity. Believing in Jesus Christ and in the transformational passion and sacrifice he underwent on the cross cleanses the stain of sin from your soul, and assures the believer of eternal life in heaven above. Encoded into the four gospels is a vast complex of myths, or Sacred Allegories, if you will, in which the spiritual mysteries of the Christian religion are contained. The mysteries of the Christian religion will gradually reveal themselves to those who contemplate on these Sacred Allegories.

What I have given you here is just a mere appetizer designed to open your eyes to the deeper mysteries of Christianity and its possible historical antecedents in the old Greco-Roman Mystery Religions and beyond. This article does not pretend to be an exhaustive or comprehensive study of all the Hellenistic elements and influences to be found in Christianity. If I have done my job here, what I have presented to you above should open your eyes to the fact that there is much more to Christianity than meets the eye of the casual observer, or even the fervent, blind faith believer as well. Welcome to the Christian Mysteries!

=====================

Sources: